Scroll down to continue

Scroll down to continue

For construction leader Dursun Kiliç and the Westermoskee board, June 21 2014 is an important day: the Alem is put on the dome of the mosque. The Alem is an Islamic symbol of a crescent moon, with partial origins in the Ottoman Empire. The Alem and the moon-shaped ornaments for the other domes and minaret are all specially made in Istanbul and transported by truck to the Netherlands. Meanwhile, resident David Wertheim and his son look out of their window at the construction site. A Dutchman with Jewish background, he has been living in one of the existing buildings for more than ten years. Wertheim tells how far-right demonstrators have tried to hijack the resistance of the residents to foster their own agenda.

In 2005, the total cost for the construction of the Westermoskee was estimated at about 16 million euros. Investment company Manderen BV was six million euros short, so director Kabaktepe sold the ground on behalf of the directors of Milli Görüș for 6.13 million euros to the municipality of Amsterdam. This land deal would financially allow for the construction of the mosque. Another part of the land had gone to housing corporation Het Oosten for the construction of surrounding houses and business premises. Additionally, a loan of € 8 million euros was issued by the bank. It was not until later that it became clear that the mosque was to be even more expensive than expected.

Illustration: René van Asselt, Elsevier (2007)

Former mosque foreman Üzeyir Kabaktepe speaks about the land deal he made with the Amsterdam Development Corporation (OGA). This deal had become necessary, as the central administration of Milli Görüş Europe in Cologne didn’t want to provide the money. Kabaktepe is of the opinion that this refusal stems from the fact that he and director Karacaer had set an independent course, different from the objectives of ‘Cologne’. Later, Kabaktepe endured heavy criticism from his supporters about the deal he made, and the leasehold construction was an important catalyst for this criticism. Kabaktepe had agreed with OGA that the land sale was to be followed with a leasehold of an annual 100,000 euros. This leasehold would be everlasting.

On the 28th of February 2006, after twelve years of struggling, the first stone for the construction of the Westermoskee was finally put into place. None other than the Minister of Justice then in office (Piet Hein Donner of the Christian Democratic party, CDA) visited the site to disclose a scaled model. In a packed circus tent erected for the occasion, he holds a laudatory speech about the project. At the same time tensions amongst the Turkish foremen are rising as representatives from the central Cologne administration didn’t get a prominent place and aren’t involved in the festivities. Former director Haci Karacaer justifies this by saying that ‘It was not just a celebration for the Turks’

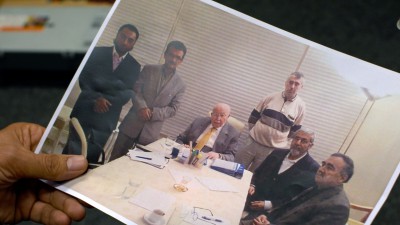

Shortly after the festivities of the first bricklaying, it became clear that the struggles within Milli Görüş were to lead to a far-reaching conflict. During the spring of 2006, Karacaer left as director while Kabaktepe’s position was under heavy pressure. Insurgent board members of the Northern Netherlands department turned against them, to the approval of the central administration in Cologne. Kabaktepe had to leave as well, and both directors were replaced by a new generation of managers. Ex-director Frank Bijdendijk of Het Oosten was surprised by these developments.

Fatih Üçler Dağ is one of the men who, in the autumn of 2006, took control over the Westermoskee project and investment company Manderen BV. He believes that there was no question of an ideological struggle about their direction, something that was posed by Bijdendijk. According to Dağ, he and the new board members endorsed the principles of integration and openness to society. He also states that there was a financial disagreement and added that the building permits of the Westermoskee were not completely in order.